The Future Homes Standard (FHS) consultation is here and while the consultation itself seems at first glance to be relatively straightforward, the whole thing is, in fact, an absolute beast. Why? Because at the same time as issuing the FHS consultation, the Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) also dropped consultations on its plans for a wholesale redesign of the underpinning calculation methodology that the building regulations require to demonstrate compliance with the energy performance of new buildings.

I decided to tackle the meal in bite-size portions, starting with the underpinning calculations and working my way up to this, my final blog on the consultation. You can find my earlier blogs looking at the changes to the calculation on the links below:

The Home Energy Model

The Solar Calculation in the Home Energy Model

The FHS 'Wrapper' to the Home Energy Model

In summary the solar industry should welcome the change to the Home Energy Model which moves from a monthly calculation of energy to a half-hourly one, better positioning the building regulations to properly account for the benefits of technological advances such as solar PV, battery storage, solar diverters, and time of use electricity tariffs.

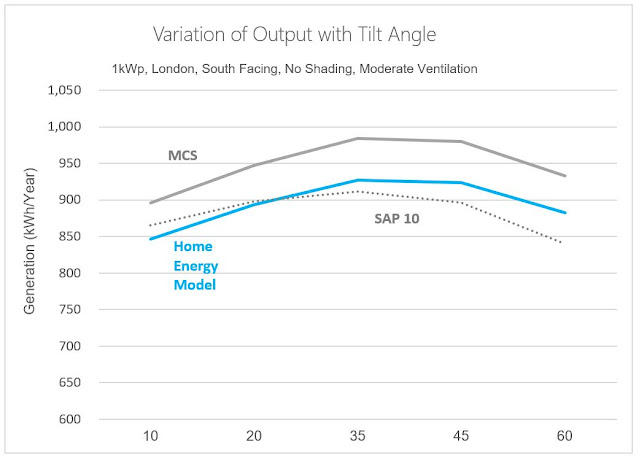

At the same time, I found a concerning calculation error in the HEM that under-represents the energy generation of solar PV as its orientation shifts away from south-facing. This needs to be corrected before the HEM can be used, and should also be taken into account when the government is assessing the responses from housebuilders, who will have been taking the results from the HEM at face value.

What's in the FHS consultation Itself?

The FHS consultation itself is on the face of it a pretty simple choice between two options for each of domestic and non-domestic buildings.

Domestic Buildings

It will not be possible to meet the standard with gas heating, so all new homes built after the regulations come into force will be electrically heated or use a heat network. For clarification this exclusion also applies to so-called 'hydrogen-ready' boilers that have been proposed by those advocating for the interests of the gas and gas boiler industry.

In this way, as the electricity grid is decarbonised over time, homes built under the FHS will naturally become zero carbon. (Note the circularity of this argument if the FHS itself only increases electricity demand without renewable generation then the job of decarbonising the grid becomes harder and takes longer, a point we return to later).

Government does not propose to change the minimum building fabric (insulation) standards for homes compared to the 2021 standards. It believes that the 2021 standards provide a good basis for the Future Homes Standard.

The Option 1 specification is based on an air-sourced heat pump for domestic heating, solar PV covering an area of the roof equal to 40% of ground floor area, an enhanced air-tightness compared to current regulations, decentralised mechanical extract ventilation (dMEV) and a waste-water heat recovery (WWHR) system on any showers not on ground floor.

Option 2 removes the solar PV, heat recovery and ventilation and relaxes the air-tightness requirement.

The table below summarises the two options and compares the key specifications to the current building regulations. At this point it is worth mentioning that housebuilders do not need to slavishly follow the specification in the building regulations. They simply need to meet or exceed the performance given by a house of that specification. For a fuller explanation of how the 'notional house specification' in the building regulations works please see my earlier blog on the topic.

|

| Selected Elements in Notional House Specification by Building Regulations Update |

Non-Domestic Buildings

Similar to housing, the new requirements for non-domestic buildings will be for electric heating and will have the same fabric as in current regulations. There is an increase to airtightness for top-lit buildings to better support new requirement for heat pump plus more efficient lighting and heat recovery.

The two options

Option 1 (recommended) solar PV to 40% of foundation area for side lit spaces and 75% of foundation area for top-lit spaces

Option 2 (not recommended) solar PV to 20% of foundation area for side lit spaces and 40% of foundation area for top-lit spaces

Analysis and Comment

Domestic Buildings

If you assume grid electricity will soon be zero carbon, you could heat an open cave electrically and it would be a zero carbon home. Once you've mandated electric heating you've met your goal and all other energy efficiency choices simply come down to the trade off between construction costs and running costs for the occupants.

The consultation lists the government's desired policy outcomes from FHS in order of priority as follows:

1. Protect occupants against high energy bills

2. Reduce energy demand of homes

3. Reduce operational carbon emissions

4. Simple to understand and use

5. Consider peak electricity demand

The consultation also presents an analysis of the estimated extra building costs and the energy bills associated with the regulated energy - that is the energy demand in the building for heating, hot water, lighting and pumps and fans, not counting energy used for electrical appliances such as TVs, dishwasher, fridges and freezers.

It concludes that Option 1 (with solar) imposes additional build costs of £6,100 compared to current building regulations but reduces regulated energy bills by between £910 and £2,120 compared to a typical existing home.

By contrast Option 2 (without solar) imposes additional build costs of £1000 while resulting in a saving of between £210 and £1,420 on regulated energy bills compared to a typical existing home.

The consultation fails to compare the regulated energy bills from Option 1 and Option 2 to those from a house built to current building regulations (I suspect deliberately, and to flatter Option 2). I have added a column on the right side of the table below showing this figure.

If the government chooses Option 2 then this will be the first time ever that a change to the building regulations on the conservation of fuel and energy results in an increase to householder's bills compared to the previous regulations, and at £580 per year, the increase is not small, in fact it nearly doubles the regulated energy bill compared to new homes being built today.

Stating that Option 2 is better than a 'typical house' is like saying that a new regulation that allows water companies to discharge 50% of sewage into rivers untreated is just fine because back in the 1920's we used to allow them to dump all of it.

Why the increase? Well simply put although heat pumps generate heat at a far higher efficiency than a gas boiler, the energy supply (electricity) is more expensive than gas, which offsets the benefit completely. Keeping solar PV in the specification generates energy that offsets the increase in bills.

Measured against the stated highest priority desired outcome from the regulations, Option 2 simply fails to deliver.

It should be remembered that tens of thousands of new social housing properties each year are also built to the building regulations. Option 2 increases energy bills for these homes too, putting some of society's most vulnerable people at increasing risk of energy poverty.

Furthermore, the entire premise that these FHS homes will be zero carbon ready is based on an assumption that grid electricity becomes zero carbon pretty quickly. Adding hundreds of thousands of electrically heated homes to the grid without at the same time taking an opportunity to add millions solar PV panels to the grid each year on the roofs of those homes will delay and make more difficult the job of decarbonising the grid, so Option 2 fails on the measure of reducing operational carbon emissions as well.

How Much Solar?

The consultation document says the amount of solar is 40% of ground floor area, but tucked away in an uncharted corner of the associated documents (the full notional house specification) is the calculation that turns the area into something more meaningful - the total panel power in kilowatt-peak (kWp), and there has been a significant change here too.

While 40% of ground floor area is unchanged from the current building regulations, the conversion factor from area to power has changed, see the illustration below.

|

| Solar PV provision in the Notional House of Selected Building Regulations |

The previous conversion factor (1/6.5) assumed solar PV panels have a power density of 153Wp/m2. The new factor (1/4.5) is a figure of 222Wp/m2. So while at first glance the solar PV provision in the specification has not changed, it has in fact increased by 45%.

Is this justified? Well the simple answer is yes. Solar panel power density has increased over time from around 150Wp/m2 in 2015 to 207Wp/m2 today, with 220Wp/m2 looking probable by the time the regulations are in force. (The table below shows the increase in specific power for Clearline fusion solar PV panels since 2015).

|

| Specific Power Density of Clearline fusion solar PV panels since 2015 |

The challenge that is being voiced by colleagues in the housebuilding industry is that some of their house designs do not have sufficient roof space to accommodate the amount of solar called for in the notional house specification in Option 1. These houses will have hipped roofs, dormer windows or other roof designs that limit the roof area available for solar.

Under current regulations these house types can be compliant because the amount of solar in the 2021 regulations is lower than the FHS and also because other improvements can be made to the specification in excess of the notional house. With the addition of higher air tightness, ventilation and heat recovery in Option 1 as standard, the opportunities to make up for less solar with improvements elsewhere are reduced.

The fact that the orientation of the solar in the notional house is assumed to be South, rather than following the orientation of the actual house makes it even harder to comply with the specification, the whole further exacerbated by the error in the Home Energy Model mentioned earlier, that grows as orientation deviates from South.

For this reason, housebuilders are saying that they cannot get behind Option 1 and will (regretfully and with heavy heart) be shouting loudly for the cheaper Option 2.

If government is minded to agree with housebuilder's arguments that they should not be required to ever change the design of houses they offer, then there are a number of potential adjustments that would make Option 1 more feasible for housebuilders:

- Fix the HEM so that it correctly accounts for solar orientations away from South

- Change the notional house specification so that the solar orientation is as per the actual house, or the best elevation of the actual house rather than assuming always south

- Change the notional house specification so that the actual roof design is taken into account when setting the % of floor area to solar. It is far more expensive to build a complex roof than to put solar on a simple roof so the risk that this could become a loophole is slim. This approach would better follow the logic of the notional house - the actual shape of the building below the roof is taken to be the same as the actual house, why not the roof? A suitable formulation would be to ask for 40% of floor area or a max-fit power based on the available roof, agreed by the energy assessor, whichever is lower.

- Finally, regulators could go for Option 1.5, half way between Option 1 and 2 - retain solar, which is the measure with the highest impact on primary energy and protects residents from increased and volatile energy bills, but to leave out the other additional measures in Option 1. This would give housebuilders design choices to allow them to 'flex' their specification for homes that struggle to accommodate the solar to match the notional house by increasing specification elsewhere.

I believe that many people that work for housebuilders genuinely want to be part of the solution to the climate crisis, and that with a few simple changes, Option 1 can and should be made to work for both the housing industry and the solar industry.